Upon entering the room where Man Searching for Immortality/Woman Searching for Eternity is displayed, I thought they were three dimensional moving structures. I first caught sight of the woman’s hand holding the flashlight and it seemed to be coming out from the flat surface of the video, facing me as the viewer. After moving into the gallery, i realized this was an optical illusion, but the video was brilliantly placed on black granite and gave the flat video an added depth that was able to make it more realistic. The figures depicted are slowly, methodically searching their bodies with a single flashlight. The black background and an eerie source of light highlights the contours of their bodies. Choosing to have a solid black background isolates the figures. The piece is solely based on the figures and their search, nothing else is there to hinder the interpretation or distract the viewer. The figures seem calm and steady in what they are looking for, which is somewhat suggested to the viewer by the title of the video. The title proclaims they are searching for immortality/eternity, but also asks the question of the difference between the two words and why a man is searching for one, a women the other. Immortality is eternity in context to a person’s life, while eternity is talking about time in general. It is curious that the woman is searching for eternity and the man immortality–it seems as if the woman is concerned with things beyond herself and the man concerned about time as it pertains to him and his life. They are both searching their bodies in the way many people look in the mirror and search for any signs of aging, worried as to what that means for them and their life. These figures are not searching for aging, however, as it is already evident in their skin and they would have already discovered it, but they are searching for an eternal life. From the title, I believe that the piece is hopeful, the figures are searching for any signs of life beyond their bodies (i.e. the soul) after they have confirmed their age and what that means for longevity of their lifetime. The age of the figures represents the time in a human life where people start to search for such things. When death seems close, people become more concerned with an afterlife and begin to search for it.

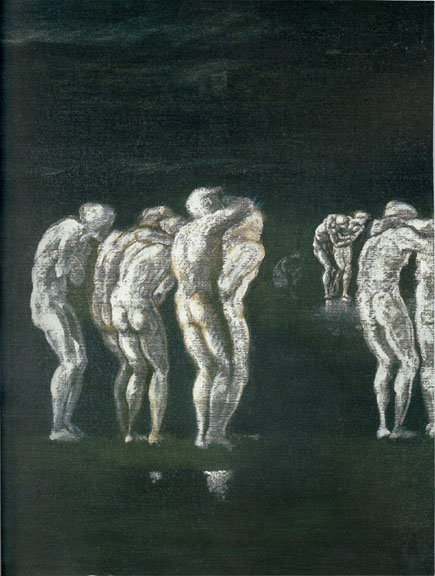

The video was made in 2013 by Bill Viola after a trip in 2006 to Windsor Castle. Viola was moved by Michelangelo’s viewpoint of the human body encapsulating the soul, it’s eventual perish, and what that meant for the soul (Royal Academy). Throughout Viola’s work he is concerned with the passage of time and claims it to be his overarching medium, not video. He states that everything develops with the passage of time, and through that his videos are able to function through duration and the corresponding thought process. In video work, I do believe duration is an intrinsic factor. A viewer’s interpretation of the video is shaped by time, how long they are watching the video, their thought process developing during that time, when they start watching the video and what they might miss. In my experience, I only saw the two figures searching their bodies, but other patrons were able to see the figures fade into the screen and walk away, receding into the background. Time changes the viewer’s perception of the video and therefore their consciousness, as Viola has proven.

Rene Magritte was a surrealist painter from Belgium who aimed to question our relationships with objects and language. Magritte pushed surrealism past the unconsciousness just having unhindered freedom with paint and made it something symbolic. Magritte choose to have a detailed and precise style that gives an unsettling style to viewers and created his ‘deadpan’ style of artwork (MoMA).

Rene Magritte was a surrealist painter from Belgium who aimed to question our relationships with objects and language. Magritte pushed surrealism past the unconsciousness just having unhindered freedom with paint and made it something symbolic. Magritte choose to have a detailed and precise style that gives an unsettling style to viewers and created his ‘deadpan’ style of artwork (MoMA).

Pierre Bonnard’s

Pierre Bonnard’s